Imagine your great grandmother crisscrossing the state with other women to collect “pennies, nickels, dimes,” for deposit at a Bank owned and operated by a Black woman. Those coins were not just money–it was a political act of defiance. It was the “agency” of hundreds of Black men and women seeking to build their dream of liberty and freedom that had been long denied.

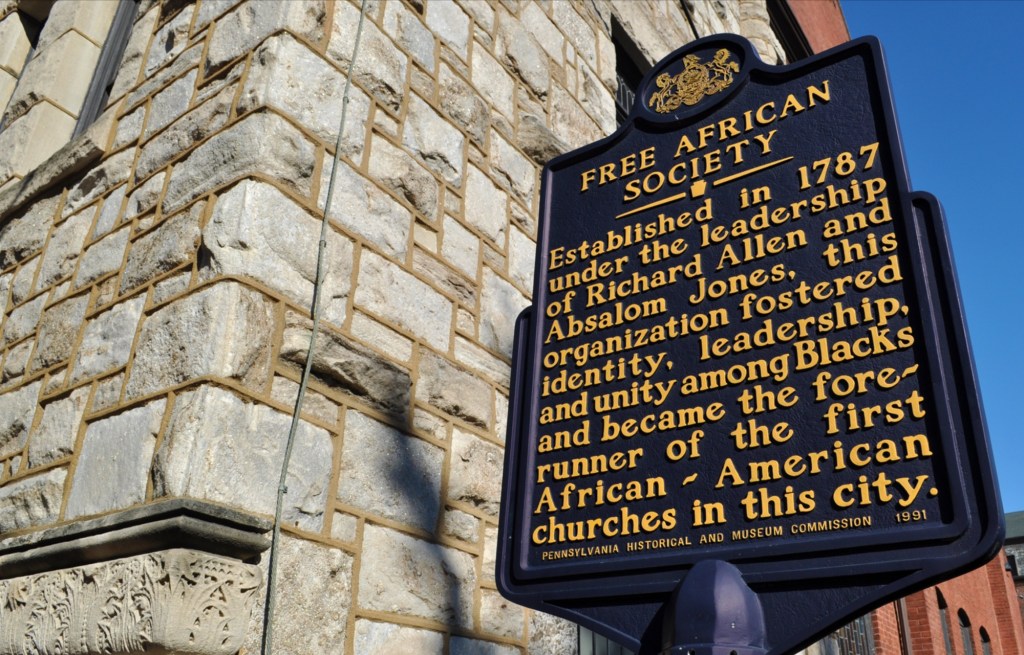

The tradition of cooperative economics in the African American community has deep roots and served as a lifeline for African Americans, offering a path to self-determination in the face of systemic exclusion and exploitation. Long before Emancipation, African Americans laid the groundwork for cooperative economics through ingenuity and necessity. Enslaved individuals pooled meager resources to buy freedom for themselves or loved ones, while free Black communities organized mutual aid networks to survive in a hostile society. The Free African Society (1787), founded by Richard Allen and Absalom Jones in Philadelphia, provided financial support, healthcare, and burial services for Black families, providing a blueprint for future organizations. Church networks were also critical and served as hubs for economic cooperation, funding schools, businesses, and resistance efforts.

These traditions continued and played a pivotal role in the African American community’s resilience during Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era. By pooling resources, sharing risks, and supporting one another, African Americans created a parallel economy that provided jobs, access to capital, and essential services, fostering self-determination and community strength in the face of adversity. Mutual aid societies emerged as a vital support system during Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era, providing essential services like financial assistance, healthcare, and burial insurance, filling the gaps left by a society that denied African Americans equal access.

Fueled by national leaders like Maggie Lena Walker, a Black woman in Richmond, Maggie L. Walker was a mother, a teacher, a daughter of a formerly enslaved cook. Rising through the ranks of the Independent Order of St. Luke’s, her vision for St. Luke Penny Savings Bank wasn’t about vaults and interest rates. It was about a widow depositing 50 cents to bury her husband with dignity, savings for education training for children, membership into a larger network of members that valued the same cause. Maggie Walker didn’t just break barriers—she rewrote the rules. “Let us have a bank,” she declared, “so that even the poorest among us can stand tall.”

And, while Maggie Lena Walker led this movement in Richmond, it is important to recognize the foot soldiers that carried out this work. The cooks, laundresses, miners, drivers, builders, house servants, and day laborers that understood the economic power of many were considerably more powerful than any of them alone.

The Independent Order of St. Luke and Black Masonic Lodges like Odd Fellows became sanctuaries. When racism barred Black families from insurance, they created their own. When banks turned them away, they lent to each other. These weren’t charities—they were acts of rebellion trying to establish a new world order to provide economic security for their families.

Here is Blacksburg, St. Luke and Odd Fellows Hall stands as a monument to that storied history. The establishment of a joint stock holding company to build St. Luke and Odd Fellows Hall speak to Maggie Walker’s unyielding truth, “Our dollars are our power.” It was a generous gift to the African American families and their descendants that met, socialized, and organized there and this legacy remains a gift to us.

Leave a comment